Science Specialist

Saturday, September 05, 2009

Science Specialist Blog has moved

http://sciencespecialist.wordpress.com/

Sunday, February 22, 2009

Sometimes it's just fun to look at stuff.

Sometimes it's just fun to look at stuff. Like, say, paints that your local artist is using. Of course it's even better if you record your observations.

Here's a paint that is enhanced by the addition of tiny glass beads. When you paint with this stuff, your art work will be shiny like a roadside safety reflector.

So, what's it look like at low magnification under the stereomicroscope?

And what if we wash off the goopy paint part and isolate just a few of those beads in a drop of water under a compound microscope at about 100x?

How did the manufacturer manage to make those beads so smooth?

And

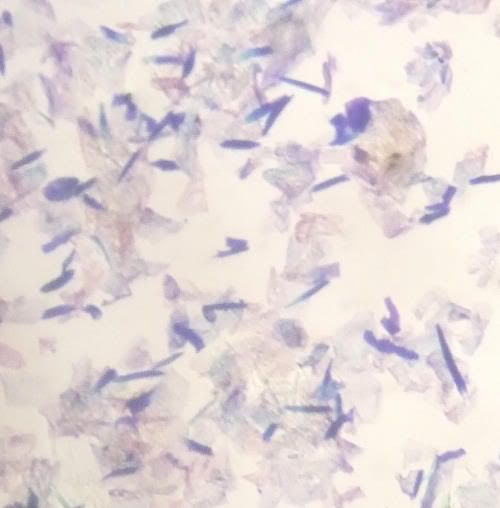

Colored mica flakes, blue and pink, give the remarkable shifting iridescence characteristic of "interference paints" made by Golden Acrylics Corp. Here you see the mica flakes in a paint sample, highly diluted and magnified 400x.

Science news this week was the story of a remarkable type of caterpillar which is a parasite on ant nests. You might know that ants communicate by smell, but did you know that ants communicate by sound too? The caterpillar makes a particular sound which the ants recognize as "I am your Queen Ant. Feed me now!" - - and lives a happy life of ease in the anthill, growing fat on the labors of enslaved worker ants.

If my migraine doesn't recur, I'll try to get back to the Miss Stone story later today. Now that I think of it, Miss Stone might have been a migraineur too.

Tuesday, February 17, 2009

Miss Stone's biology -- part 1 of ?

My high school biology teacher, Miss Stone, taught a high-intensity high-speed course for the aspiring science major. She taught it like a freshman course in a good university: fast lectures, a lot of reading, and high expectations for retention and comprehension. She even added extra after-school sessions in spring for those who were interested. Students who did well in the course and took the extra sessions would reliably pass the AP exam.

And then there was … the Microbiology Challenge. In the middle of the year, an extended lab project required us to grow yeast cultures in test tubes full of nutrient broth. She told us the goal of the project (which I don't remember now), and gave us practically no instructions. Week after week, puzzled and frustrated students (myself included) would find their test tubes, once again, contaminated. Where there should have been a healthy yeast population, there was a cloudy stinky mass of other single-celled invaders. I remember her peeking into the microscope and gleefully asking somebody, "Is that your yeast or your pond water?"

After a few weeks of this, 85% of the class that was still stuck; but we began to notice that 15% of the class seemed to know something we didn't know. They used a number of techniques such as passing a flame over the opening of the test tube every time they opened it for any reason. And their cultures did not get contaminated. Other students began to ask those 15% what they were doing, and word got around bit by bit.

Eventually, after the end of the project, the class as a whole was given the half a dozen standard microbiology methods – flame and so forth—that would allow anybody to do this culture growth successfully (and would have reduced the six-week project to a one-week project).

I still don't know where those 15% got the advance information. Did they corner the teacher after hours and demand extra help? Were they the children of professional scientists? Did they take the bus to Harvard and dig in the science library there?

The real agenda of this project was never stated. I can guess at two things Miss Stone might have had in mind.

- Preventing contamination is really hard. Until you've failed twenty times in a row you won't appreciate this.

- In real life, the "answers" are not given to you in advance. You have to use any and all means (teacher, parents, Harvard library) to solve problems that nobody even told you would exist in the first place.

These are both laudable purposes, but I left with a feeling of frustration around (2). In terminology I learned later in life, I would have said we were "set up to fail". Or perhaps it was a "sink or swim" type of test. Students who – somehow – had already at age 15 grasped lesson (2) were able to demonstrate it and appreciate the success it brought.

Next instalment soon. . . running out of time here . . .

Saturday, February 07, 2009

Density and memory

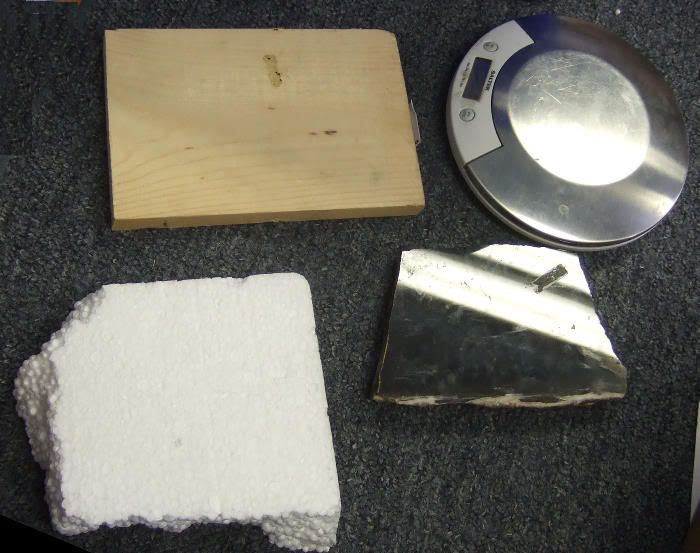

Today's lesson topic was density. In keeping with Montessorian principles, the same materials can be presented to different age groups, with different levels of discussion. Thus, the K group simply holds and feels the three objects (see picture) and learns the word "density", where the EE group also weighs them. As soon as they get to long division in math class, we could bring the same objects back, measure their volumes by the Archimedean method, and compute the density.

Here are the three objects of different densities (and the scale).

Also in EE we can refer to other objects of higher density. I figure when they jump up and madly run for their astronomy books, desperately eager to show all the pictures, this is a good sign.

Last week's Science Magazine news-of-the-week gave us a discussion on Bacillus Thuringensis. For the K group, we go for the key concept: "These germs kill bugs that eat crops" (good timing, as the Gardening class has been suffering from an aphid attack on one of their cabbages). In EE, we point out the disturbing evolution of Bt-resistant pest insects (and alert students ask how severe is the threat to beneficial insects). Left for next year is the actual content of the article, which had to do with remediation strategies for Bt resistance in the context of genetic recombinants. And several years away are lessons on Monsanto politics… too complicated for now.

This week we did a memory experiment, which was so much fun I think I will add it to the standard weekly protocol.

Start by asking "who remembers last week's News Of The Week", and notice the unanimous response (sudden surprise: omigosh, I just realized I have absolutely no idea!). Then, drop little hints, ("does anybody remember trying to learn a long name. . . something about germs. . . the initials Bt…") and watch as the lights go on one by one around the room. I should probably videotape the whole sequence as there is a ton of good neuroscience in it. Like after about 9.2 seconds people start remembering the News from two or three weeks ago instead, and so on. Or, next class, how much faster will they remember Bt? (average time until the mouth bursts open in an "aha" response: might have been 30 seconds this cycle, will it drop? Linearly or logarithmically? etc)

Of course we also had stinky stuff and blew things up … goes without saying…

Tuesday, January 13, 2009

Local business helps again.

This time it's the Feather 'n' Fur Animal Hospital of 9125 Manchaca Rd. I got into a conversation with them last December when I realized how much microscopy they do - - counting white cells, examining tissue samples, etc. One of these weeks I'm going to get around to buying a good batch of stains so we can prepare really vivid slides for class, but in the meantime they volunteered to give me some nicely stained genuine veterinary slides for the class. So I brought in a blood smear and a little ear cytology slide.

One of the K students brought in a splendid gastropod fossil, but somehow immediately segued to arthropods, and so we learned a little bit of greek (arthros, pod, gastros) and somehow ended up talking about scorpions. They do love to tell personal stories in these classes, and last time I checked my Official Theory Of Learning, I think it said that when the lesson becomes personal then the learning becomes permanent. Not only were we regaled with everyone's tales of Scorpion Encounters, but one of us claimed to have a house and yard practically chock full of the little critters. Now if that is you, please do send one in for class (feel free to kill it first if you like), because I have a UV light and it is really quite neat seeing how scorpions fluoresce in UV light.

So there you have it - - once again the K ran out of time without even getting to the Question Box. We'll have to start the class next week with the Q B.

The EE class is divided into two sections - - half the class has Science Guy while the other half has Gardening Gal, then they swap - - and it's funny sometimes how the two sections will take off in different directions from the same starting point. After sharing today's news (Possible Breakthrough Malaria Vaccine), and the first couple questions, one group got onto Black Holes and - - that was it - - you get somebody excited about Black Holes (and light and perception and gravity and density) and they don't want to talk about anything else for the rest of the day.

The second group marched cheerfully through their questions and moved on to the microscopy instead. Of course they all want More Power in the microscope, so if you find an opportunity on a nice 1000x oil-immersion scope (stereo, with the nice wheel-driven platform), or a cheap used electron microscope, don't let it get away. (While you're at it, we could really use a particle accelerator around here).

By the way, I heard a glimmer of interest last fall about First Robotics competition. At the time things were too hurried and maybe most of our group too young. But I wonder if now is the time to start thinking about it for next fall?

Sunday, December 07, 2008

Here are some things I have learned about K/elementary science.

Styrofoam balls are always good.

Experiencing the lesson with your whole body is sometimes good.

Certain situations are guaranteed disasters.

This week, the K class built insects with styrofoam balls. This basically entails learning the vocabulary head, thorax, abdomen, six legs, antennae. But the bottom line is that everybody loves a styrofoam ball demonstration. We will do water molecules, spiders, and inscets every year; and if somebody figures out 100 more things that can be done with styrofoam balls, we'll do them all. (Now I must away, to eBay, to find a mountain of styrofoam balls and perhaps a volume discount on pipe cleaners).

This week in particular was the right time to build insects because of last week's news item about termites. Termites cannot digest cellulose (i.e. wood), and they rely on single-celled eukaryotes in their gut to do this job for them. However, there's still a problem with this picture: there's no protein in wood, so how can anybody survive on a diet of pure wood? It turns out that neither the termites nor their pet eukaryotes can do it, but inside the eukaryotes are a colonies of a species of prokaryotic single-celled organisms, who can't digest wood, but do have the remarkable skill of capturing nitrogen from the air (a rare and special ability better known for its appearance in bean root nodules). Once you have nitrogen, you can build proteins. (The evidence for this was found not by cultivating the prokaryotes, which is difficult because they can't live outside a termite, but rather by sequencing their DNA, which led an alert scientist to say something like "Hey, I recognize that 4000-base DNA sequence! That's a nitrogen-fixing enzyme!").

The natural followup to a news item about termites, of course, is a lavishly illustrated library book about them. This of course leads to a lively discussion about termites, houses, queens, workers, styrofoam models, African termite mounds and so on; which brings me to another point:

Do you have any termites at your house? Because we sure could use a couple for the microscope. Maybe you have some in the privacy fence around your back yard? I just don't seem to have any termites handy, and the whole K class sure would be grateful if you could send us a few. Feel free to douse them (the termites, not the K class) in isopropanol before sending them to school.

Experiencing the lesson with your whole body is something I keep re-learning from my daughter. I remember last year a discussion about dolphins, and diving, and fish - - and she interrupted to make sure we all had a chance to do a sort of diving-swimming movement to really get the point home. And she does it all the time at home, even during Story Time. A character in the Story might dance with joy and fall down: she has to interrupt the story so she can dance with joy and fall down. This completes the communication. The words, the concept, the complete grokking.

This is why the live-action demo skit for the elementary class was to include seven kids acting the part of protons, while an eighth one pelts into them as a secondary cosmic ray in the form of a neutron, causing a nitrogen atom to turn into a radioactive Carbon 14. (Ultimately this lets us understand the evidence that proves global warming is man-made). But certain situations are guaranteed disasters and these include seven elementary kids packed together. Instead of a nitrogen nucleus, they formed a giggling rugby scrum, and simply could not be brought back on topic. (on the replay, with a second group, I kept the proton kids neatly spaced about a foot apart, and we did much better).

Tuesday, November 25, 2008

More fun w microscopes

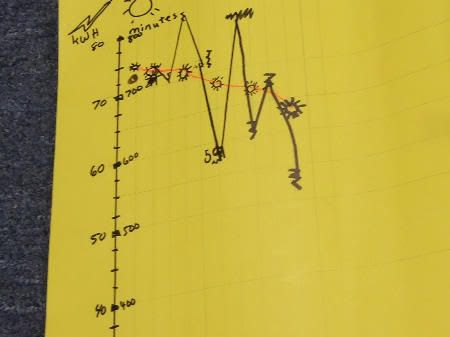

Continuing progress on the class project to track productivity of my solar energy panels and day length:

Microscopes repaired!

Both microscopes in the elementary classroom broke last month. I finally tracked down replacement lighting (plus I jiggered with the eyepiece alignment, an area of mechanical engineering where I was definitely in over my head, but I escaped having done no harm and perhaps slight improvement).

The new light source is a big improvement: as you can see the colors are much more true than the old one that burned out.

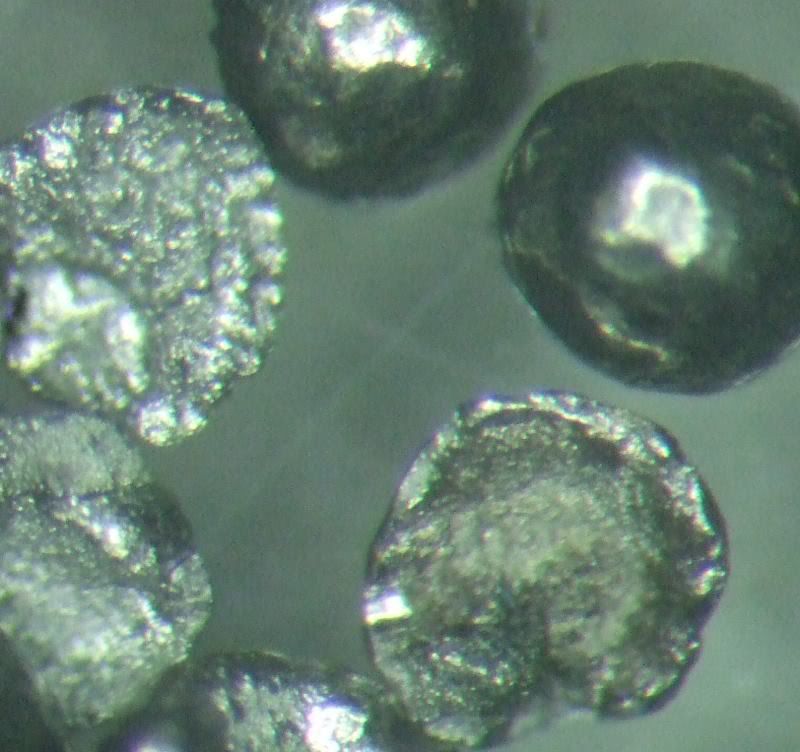

There is an industrial process called Shot Peen, or, as I like to call it, "world's tiniest hammers". In order to work-harden the metal (of something you are manufacturing), it would be good to hammer it all over. But instead of using hammers, they use a huge quantity of tiny steel balls, shot through a sort of fire hose (something like sandblasting). These pelt the metal and effectively hammer the surface. I managed to acquire some of these, used, and brought them in.

In the microscope you can see the effect that the impact had on the steel balls.

In one group, there was a sudden mass desire to look at blood in the microscope. A diabetic student who has a glucose test kit kindly offered a drop of blood. If you do this at home, dilute the blood with salt water - - that way you can see the individual cells instead of just seeing a swirling mass of red.

The cells tumble slowly around so you can see some of them edge-on, or tilted, or face-on just looking like circles. It gives you a nice sense of the actual shape of the cells.